Marilyn Holsing painting in studio

Elizabeth Johnson: In your Artist Statement on your website you say, "My imagined worlds don’t obey the rules of the real but operate in liminal places where they mesh or collide. Where is the edge of the rain, the exact place where it begins and ends? How can a waterfall magically appear out of nowhere or abruptly end?"

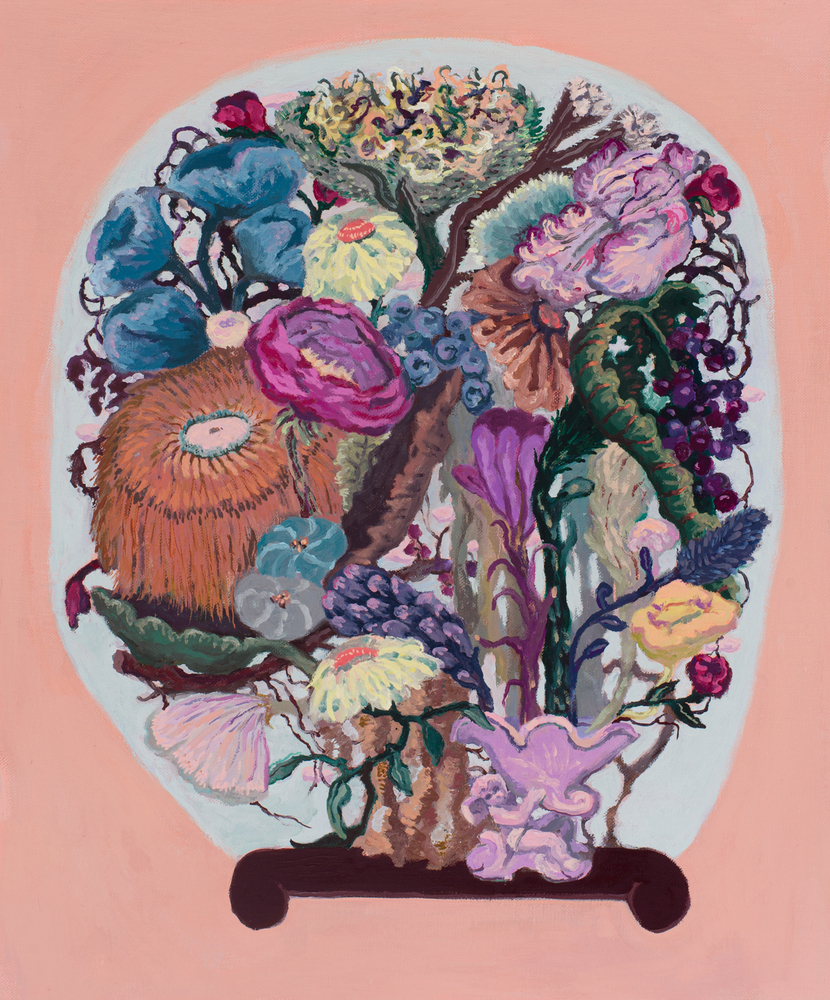

Your recent pieces Clawfeet, Elegance, Veranda, and Fondly explore the imaginary space created inside various shapes, which recall Victorian bell jars. Do you depict transparent containment because it combines painting with dioramas? How did you discover this idea?

Marilyn Holsing: I started making dioramas several years ago for a show at Gallery Joe. The first one was two scenes depicting different stories about my invented narrative of Marie Antoinette’s life, made of paper and paint, with sounds of the forest and voices, and an animated sky of moving clouds and birds. This led to making a more ambitious diorama of eight by eight by four feet with 3-D figures, animatronics, sound and video based on Fragonard’s The Progress of Love.

In these and others, I realized I needed to explore facial expressions more closely, and I started making small six-inch busts sitting on a variety of little legs. For protection, I put them in cloches and included environments to create narrative tableaux, not unlike the terrariums I have made at home. Encasing these things in glass highlights their preciousness and their need to be protected from everyday life. In Susan Stewart’s book On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection she writes about still lifes as “arrested life,” a phrase I embrace when thinking about the dioramas and the paintings.

Clawfeet, Oil on linen over panel, 30" x 24"

MH: These small dioramas (twelve by twelve by twelve inches) are in my studio, where I can study them not necessarily to make paintings from but to think about. In a way, they are cruel––I am confining these sculptural, almost human beings; yet also, observing light reflections on glass, distortions, and background shapes. The cloches set things apart, creating separate environments that are made significant by their detachment.

The paintings you listed came from studying how light and transparency works in these glass containers and imagining landscapes in them. Sometimes the space of the contained landscapes is deeper than the space or room where they reside.

As for the imagery, it starts with vague sketches in my sketchbook. I wanted a break from figures as a studio project, since invented figures had been my main subject for more than a decade. Most of the imagery in these new paintings are supplemented by observation from nature, botanical illustrations, and gardening.

EJ: The bell jar “device,” let’s call it, mixes 2-D and 3-D, and it seems significant that you use limitation, a controlling vessel, to picture activity. The bell jar pieces also conflate what's attached to the glass with what's contained. What freedoms and restrictions does the format offer you?

MH: It began as a test: could I create a space within and simultaneously contend with what happens on the shiny surface, as well as the distortions of glass? And what could happen outside the bell jar/cloche?

Veranda, Oil on linen over panel, 30" x 24"

Fondly, Oil on linen over panel, 30" x 24"

MH: The landscape elements are pure invention: they begin with abstract color blobs that I manipulate into flowers, leaves, bushes, sticks, stones, etc. Constriction adds to their drama, sometimes flowers or leaves are pressed against the glass almost straining to escape.

Part of the challenge of these pieces is making the glass transparent at the same time they depict what is reflected on the surface. I combined observation of the actual cloches in my studio with photographs of glass cloches from the internet. I was particularly interested in what happens at their edges when they seemingly disappear into the background.

The space inside the container is deeper than surrounding space: a dense forest of plants, vines, etc., contrasts with the quiet of the room or setting of the cloche. After about half a dozen cloche paintings, I have moved on because they became confining and in danger of becoming formulaic––ironic since they are meant to confine. I may go back but they have opened other areas for exploration.

EJ: I believe you when you say in your Artist Statement, "A large part of the joy of working in the studio is the opportunity to explore ideas not knowing in what direction they may lead as my recent landscapes evidence. The landscapes are twisted and manipulated into places where an unknown narrative could take place, in place of the figure, the land, the flora, rocks, branches, and puddles become metaphors for the anthropomorphic. There is no signifier of a specific location; they are more about the sense of place and its effect."

Marilyn Holsing's Studio

EJ: Your pieces seem to mesh the cool removal of scientific or narrative inquiry with playful display. Does your anthropomorphic mean joining a landscape exterior with human feeling or interior? perhaps signaling being half natural and half human?

MH: Yes, I think you have grasped it. In developing the “color blobs” that are the starting point for the flora of my paintings, the sense of human movement is instrumental to their progression, position, and interactions of flowers, leaves, branches, stones, etc. These could be viewed as scenes for some sort of story. My earlier Young Marie work directed the narrative, whereas with this work the narrative is open-ended and implied.

EJ: I share your admiration for Rococo and Fragonard. In The Library recalls the garden statuary in his love scenes, and feels especially mysterious: fabric conceals a background, the horses are liver spotted, the mirror seems to prophesy. It's complete, hermetic. What’s your take on this piece?

MH: It has personal history, and I think it is the impetus for much of this work. At my mother’s 99th birthday party, I was standing in front of her mantle, a memory and feeling that is very vivid after many years. I wasn’t thinking about anything specific while standing there other than simply looking at a vase of two horse heads. When I was cleaning out her house, I took it to the thrift store and have regretted it since. The memory of this vase began to obsess me, I tried to find the same one on eBay, but I realized I did not clearly remember it. In my search I stumbled on other horse-themed vases, including a double horse one, and I began collecting images of these vases. The image is loosely based on these double horse vases...

In the Library, Oil on linen over panel, 30" x 24"

MH: ...The oval behind the vase began as a mirror that became a landscape painting, but it could be a landscape reflected in a mirror. Much of the imagery of this painting was not preplanned but came from reactions generated while making it. All my paintings begin with a colored imprimatura of random colors; in this case, it must have included several browns. The browns became wood paneling, and to break up the brown, I invented the turquoise curtains and created the oval mirror/landscape. The fact that I grew up with wood paneled rooms and horses adds to the personal connection.

Marilyn Holsing working in studio

EJ: Which of your pieces best illustrates your Artist Statement sentence "I usually think I am doing this, but learn I am really doing something else, and I only learn this as I am working"? Do you feel like you back into balancing sections of visual and psychological mystery in your pieces? Do you consider your work surreal?

MH: In The Library was not intended to be an interior. But as it developed, it made sense for me to make it one, and then my intention was to make the background into wallpaper. But it worked far better as wood paneling, a case of the painting telling me what it needed. The mirror/painting in this work is another example. I love surrealism, and it shows up in my work without conscious calculation.

EJ: I connect another Artist Statement idea to your collaged garden pieces. "Clashes between the ways I think about the landscape and its actualities continue filtering into my imagination." This fits with the play of forces within Formality, Picnic, Merlin, and Stein. These pieces make me think of your flowers as emotional thought bubbles that are anchored to more rational containers or settings. Merlin might be the most extreme juxtaposition of real and imagined as icy lace on a severe table balances floral abundance. What would you say Merlin reveals about the clash between thought and actualities?

MH: Formal, Picnic, and Stein share the idea I noticed in the paintings by Rachel Ruysch, and other 17th and 18th century painters: their images often appear to have been made in a dark matrix. These three paintings share dark matrixes and tiny containers that would be unable to hold all the foliage.

Merlin, Oil on canvas over panel, 14" x 11"

MH: The flowers are not unlike “thought bubbles,” which may be overwhelmed by all the ideas we may have.

The flowers begin as color blobs that frequently simulate vicarious movement.

Formality, Picnic, Merlin, and Stein are part of my Diminutives series. The containers are intentionally small, doll size. I find there is a feeling when I hold these impossibly tiny objects of this size that I cannot verbalize but it engages and intrigues me. As part of this series, I have been making small paintings (fourteen by eleven inches) of these really tiny objects.

Perhaps it has something to do with “meta”? Setting on a well-used piece of cloth draped over a shelf between two walls, Merlin illustrates the clash of thought and actualities, as the elaborate flower arrangement grows out of an illogically small glass container reminiscent of a laboratory vessel.

EJ: Considering Rachel Ruysch and Otto Marseus van Schrieck, the two 17th century Dutch painters you mention in your Artist Statement: Does the Dutch style of obscuring items behind other items in complicated compositions and relishing plenty to the point that the whole outweighs individual parts dovetail with your use of cloche or bell jars and mysterious drapery?

Contained, Oil on linen over panel, 24" x 20"

Exposed, Oil on canvas over panel, 14" x 11"

MH: The forest/still lifes of van Schrieck and other sottobosco painters are something I saw as a child, perhaps in a museum or a book and was entranced by and I still am. They are so illogical and mysterious and could be the setting for some gothic tale. Their superrealism is of interest for its rich pattern, texture, and color, the details remind me to embellish my invented flora.

I respond to the way these painters depict abundance and focus on a world of plenty and beauty––painting flowers and plants realistically is not my goal––and it is almost as though these painters can’t load enough images into their work.

Elegantly curving leaves and petals motivate my treatment of the shadowy matrix; for instance, as in my painting Picnic.

I am responding to their density, elaborating and incorporating my own tangled stems, leaves, and seductively painted flowers.

Stein, Oil on canvas over panel, 14" x 11"

MH: In my painting Fondly, the tendrils, vines, and leaves of the inside arrangement partially obscure the background landscape as seen through the window behind the cloche, as do the surface reflections. Surface reflections hide parts of that landscape in the background, suggesting that the landscape elements are inside the cloche, an ambiguity I embrace. Picnic and Stein form a shadow-like shield of middle ground on top of the background blocking our view, reading as an opaque or a semi-transparent shadowy area.

I don’t know what is behind the curtains in paintings like In The Library and Ever So: they were mainly the result of necessity, the space needed to be divided. I embrace their mystery and the possibilities they present for future work.

EJ: You mention that you admire the palettes and inventiveness of Inka Essenhigh and Lisa Yuskavage. You seem to use a jewel-like palette centered on deep purple, red, green, and blue, as opposed to painting flowers and plants in daylit colors. Would you consider your palette as evocative of internal thought more than realistic exteriors?

MH: Yes, I am not trying to paint realistic exteriors or lighting. I love color and have jumped into it with both feet after several years of using a very limited palette in the Young Marie series.

My color is rarely preplanned except to exclude colors I feel have become a crutch. The palettes of these two painters and their paint handling are so lush, masterful, and inventive.

Events, Oil on canvas over panel, 28" x 24"

EJ: To me, Events feels like In The Library. Something pleasurably weird is going on. Two incomplete mirrors or plates on each side really work compositionally. Also, the central still life seems to float while the plates rest on a wood-grained table. Did you mean to baffle with two points of view? Did this just happen?

Mirror, Oil on linen over panel, 24" x 20"

MH: Yes. It just happened.

Events may be the oldest painting in this show and is baffling for me, as well, partly because I usually work in series, and this did not lead to other work. The mirrors are meant to be seen as mounted on a wall and the foliage and vase in front of that wall. I sometimes think of the mirrors as being near my mother’s mantle with a fuzzy double reflection of me, but she did not have any mirrors like these.

––Elizabeth Johnson

(elizabethjohnsonart.com)

edited by Matthew Crain

(@sarcastapics)

February 2026

Marilyn Holsing painting in studio

About the Artist

Marilyn Holsing lives and works in Philadelphia. She has exhibited her work in numerous solo and group exhibitions throughout the Mid-Atlantic region and beyond, including, The Delaware Contemporary in Wilmington, Delaware; Melanee Cooper Gallery in Chicago; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge; the ICA at the University of Pennsylvania and Field Projects, New York. Her work is included in public collections such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Woodmere Art Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Fidelity Investments. She is Professor Emerita in painting at Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia.

___

“An Ohioan by birth, I have lived and worked in the Philadelphia area for decades, moving here to teach at Tyler School of Art after graduate school. My undergraduate degree (BFA) is from the Ohio State University and my graduate degree (MA) is from the University of New Mexico. I retired as Professor of Painting a few years ago, but I have continued to work in the studio in a variety of media. My practice has branched out into new directions, such as dioramas, while continuing my commitment to painting.

In these years I have lived in the city followed by a move to the suburbs. One of the joys of life in the suburbs is the opportunity to garden. Not only do I grow flowers and shrubs, but I like re-designing the plantings, interests that reveal themselves in my studio work.”

Elegance, Oil on linen over panel, 30" x 24"