Studio Interior with Cakes,

20" x 16"

Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel

Elizabeth Johnson: Here’s a sentence from your interview The Way I See It in Trebuchet Magazine:

"In contemporary art there is a tendency to try to pull threads of narrative significance from the creative choices made by the artist.

Why this window? Why this time of day? How do these choices work together to construct a discourse that we can read and read against? All the while we wonder what the work is trying to say, when the wider, often more rewarding question is, what is the work trying to do and is it working?"

What are the markers or qualities that tell you a painting is starting to "work"?

Peter Van Dyck: There are two levels of a painting “working,” for me. The first is getting from the blank canvas to a legible depiction of the subject that has a sense of space and light. That happens quickly for me, and it’s fairly obvious when it is or is not there.

However, that is a very low bar for success. The next level of “working” is looking at the painting and being convinced that I’ve made something wonderful.

That feeling is hard to define and there’s no concrete indicator of it.

Peter Van Dyck's Studio Window

EJ: Also, in this interview you talk about allowing changes throughout the process of a quick sketch, a larger drawing, and the canvas. If the finished work is a summation of all decisions large and small between first encountering a space and you rendering your central experience of it, how do you create the curved look of your spaces? Is it both imagined and measured? Do you ever use Photoshop Warp mode? Why do you choose oil canvas glued on board?

PVD: I paint on rigid surfaces only because I tend to be pretty rough with the surface and I want it to be able to withstand whatever abuse it gets.

I don’t use any photography or digital imaging to make my paintings, simply because a photograph doesn’t contain the experience I’m trying to convey, which is what it's like for me to be in the world as well as the mind-blowing fact that the world is here at all.

As for the curvature, the simple explanation is that it results from taking on a wide enough view of the subject to necessitate turning one’s head to take it all in. The more exhaustive explanation is as follows (which most painters will already know).

Any sight measurement made from three dimensions to two dimensions is made relative to a picture plane, which is the imaginary window we look through to make two-dimensional images of the three-dimensional world. Traditionally, linear perspective is only considered a convincing representation of the view through the picture plane when it depicts a very small section of the field of view. Should the artist want to depict more space than fits into this section, they must turn their head and/or body to see it. As they look around the space, they are creating more picture planes, each being angled differently based on the direction of their gaze.

Studio Sink, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 22" x 24"

Peter Van Dyck in his studio

PVD: The measured angles and proportions of the subject as projected onto the picture plane change depending on how it is oriented relative to the subject; hence, each movement of the artist’s attention creates a different set of angle measurements.

Taken together and laid onto the canvas, these multiple picture planes add up to a curve. That is a simple technical fact about the geometry of light and rendering three dimensions into two dimensions on a flat plane.

However, since there’s no objective order or sequence in which a person attends to or absorbs a space or subject, there can be no single, correct set of picture planes to describe that experience.

So, when the artist adjusts their body, moves their head or directs their attention to various elements in the space, they are effectively moving and resizing their picture plane along with their attention.

They must imagine these different picture planes, what size and proportions each might be as well as how they might overlap, merge or otherwise interact with one another. Hence, there is no “objective” way of interpreting this because it is contingent on the very particular and vastly differing ways that an individual might experience a space.

EJ: Does creating a curved spatial continuity organize your painting, and then you vary emphasis and focus on smaller areas?

How do you know when you're done?

Yellow Cake Still Life with Flowers, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 16" x 20"

PVD: I start with the overall, unified frame of space, trying to create an overarching spatial matrix that then modifies the appearance of the objects that it contains.

Unfortunately, I’ve never finished a painting. I find that if I try to finish something, all I’m really doing is executing a set of predetermined decisions, and that just runs counter to the spirit of how the painting has been created up to that point.

It feels very unnatural and awkward and almost never makes the painting better. So, instead, I tell myself that I can work on a painting for as long as I want. At some point I lose interest, or I get too frustrated, or something causes me to put it aside. I almost always tell myself that I’ll work on it more, and sometimes I do.

I see the paintings as being whatever they are at any given moment in their development, and I try to take them on those terms rather than think what they're supposed to look like.

Ballard from Steve's, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 32" x 36"

EJ: You state your purpose clearly in the interview when you say,

"I’m not interested in the photographic logic of representation, and what I do is not photorealistic, but it is what I see. That’s the misunderstanding about what photography is. People think it’s what you see, but it’s not quite that. It’s easy to understand how visual culture pushed illusionism as realism and it became that way via a language of forms, a vocabulary of light hitting a form. Whereas, what I want in painting and drawing, is to convey ideas which have a different expressive language. For me, those ideas have a radical relationship to certain forms, while they have only a tangential relationship to the optics that make up photography."

Your pieces curve forms like the warp created by Photoshop, cameras, and computers. Cézanne broke his subjects into geometric forms to make space.

How does your work relate to or differ from his? Does working in continuous curving space like digital images made of billions of bits of information link you to the digital age?

Peter Van Dyck's Studio

PVD: No, not to the digital age per se. But I do think that painting can be seen as creative information processing.

My understanding of Cezanne is that he saw the world through the lens of simplified geometric solids, and I am a hundred percent sympathetic to that way of understanding the physical and visual world. In fact, I find it almost impossible to register any experience without first engaging it in a tactile, volumetric way.

It seems to me that Cezanne is not constrained by this need for a dominant, almost tyrannical organizational structure. His overall organization emerges more organically and less predictably from the moving of his gaze around the subject.

My dependence on a unified spatial framework prevents me from working more freely.

I’ve tried throughout the years to liberate my imagination from this kind of order. Though my decisions feel arbitrary and I haven’t been able to believe myself, I don’t have any choice but to continue trying.

EJ: I am intrigued by how under drawing animates your paintings.

Cupcake Trio sports an unfinished shape. Outlines for orienting cakes and objects in Yellow Cake Still Life and Yellow Cake Still Life with Flowers help us see your precise compositional planning.

How do you think about these persistent indicators of your way of seeing? Are they chance-based? Do unfinished areas help communicate the working time of your pieces?

Yellow Cake Still Life, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 16" x 20"

PVD: It is never my intention to leave areas unfinished or to intentionally preserve evidence of the process.

These things just happen when I try to honestly engage the problem of making a painting. It’s like if I’m trying to make something in my workshop and I’m busy trying to get it to work and that has me reaching for different tools or materials and discarding them and not putting them away since I’m really focused on making something and the state of workshop itself starts to have a character to it that is totally unintentional.

The viewer is like someone who comes in and instead of seeing what I’m working on, they see the workshop and for them it has a certain poetic quality. The irony is the viewer gets both my process and what I’m trying to make.

EJ: Perhaps more removed from the drawing process, the lines on the surface of Martin Street, especially curved lines over the sidewalk planters, make me feel distant from the image, like scratches on a photograph.

They could also indicate physical presence such as energy, or quantum particles. Do the lines indicate that your paintings eternally link personal objects with the empty spaces they occupy?

PVD: Perhaps they are the beginning of an attempt to introduce the plants that were in the planter.

I was probably trying to capture some sense of their gesture before starting to paint them in...

Martin Street, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 32" x 34"

PVD: ...Much like the drawing, the texture of the surface is just the result of the process. While I don’t create it intentionally, I must have some aesthetic bias in that direction; otherwise, I wouldn't be okay with leaving it.

EJ: If, to you, experience is more important than narrative, what role does memory play while painting the passage of time, light changing throughout the day, or your personal still life objects? Does memory and story interfere with linking moment and place? Is Bermuda Lawn less curved because it is less personally related?

PVD: On-site painting provides the experiences that are then recalled in memory back in the studio. Memory is the filter of meaning in so far as that you remember what strikes you. If I don’t remember something, by definition, it can’t be very meaningful to me.

As far as a story goes, there’s only ever one story that I’m trying to tell, and it is one that I have only seen told by paintings. I have to let the paintings tell that story.

The curvature has only to do with how wide the angle of the view is, it has nothing to do with a stronger personal connection to a particular subject. I haven’t thought much about the personal nature of the objects. But the whole thing is personal.

Bermuda Lawn, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 16" x 20"

Still Life with Deck and Globe, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 39" x 36"

EJ: Is the rectangle of blue stapled to the sky in Martin Street perhaps a foray into collage and sculptural effect?

Is this device related to red and pink paper scraps taped to the window in Still Life with Deck and Globe?

PVD: The pieces of paper were intended to be removed, and I think I have taken them off.

I like what I call “clean color” in painting, meaning color that strikes a decisive, unmodulated note and is unsullied by demands for it to merge with the surrounding illusion.

My paintings tend to start with decisive color but as the painting becomes more naturalistic, that clarity gets lost in creating a seamless illusion––and I don’t like that.

By adding a completely uniform piece of color with absolute boundaries (in the form of a piece of colored paper) I feel like I’m restating that intention for myself, and it clarifies the painting as a whole.

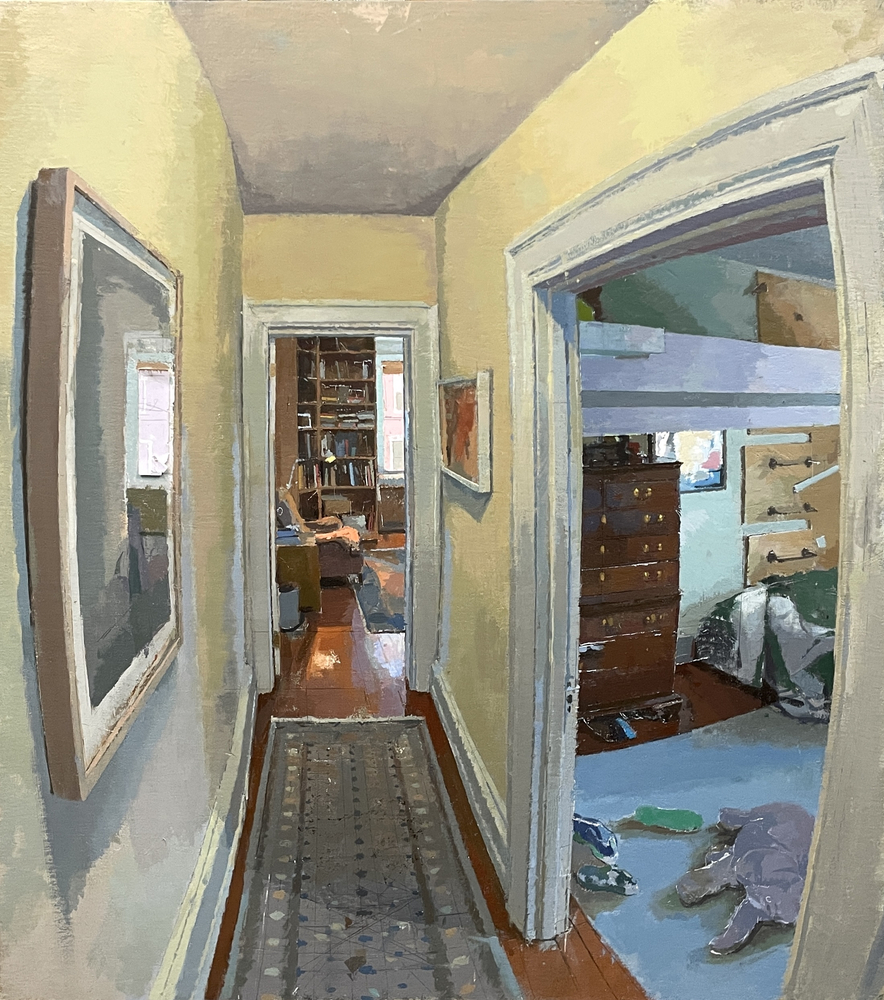

Hallway with Sam's Room, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 36" x 30"

EJ: Hallway with Sam's Room piques my interest, since I can't quite work out if I am looking at mirrored images in Sam's room, or a complex jumble of parts of architecture. Are you pleased, as I am, when space is mysterious or do you want viewers to be able to easily explore each inviting deep space they encounter in your work? Is misapprehension not a chosen part of your work?

PVD: That painting has caused me all kinds of trouble because of the information inside that bedroom. The arrangement and the structures of that room are very strange, and the view I had of them made it doubly difficult to describe them.

There's a dresser tucked under a bed that hangs from the ceiling and one wall. Then at the far right of that opening is a climbing wall that I made when I hung the bed so that Sam could climb up to it. I don’t think I was very successful in describing that in the painting, but I’m fine with the ambiguity.

While misapprehension is not my goal, I very much enjoy mystery in painting. I think misapprehension is integral to a sense of mystery.

––Elizabeth Johnson

(elizabethjohnsonart.com)

edited by Matthew Crain

(@sarcastapics)

Peter Van Dyck in his Studio

About the Artist

Peter Van Dyck was born in Philadelphia in 1978. He studied painting and drawing at the Florence Academy of Art in Florence, Italy from 1998-2002. While studying he also taught in the program from 2000-2002. He returned to Philadelphia in 2002 to paint in his own studio and began exhibiting his work in numerous group shows in Philadelphia, New York and San Francisco.

He has had solo shows at John Pence Gallery, San Francisco; Eleanor Ettinger Gallery, New York; John Pence Gallery, and The Grenning Gallery, Sag Harbor, and Gross McCleaf Gallery, Philadelphia. In 2003 he began teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts where, in 2011 he became an Assistant Professor in the Certificate/BFA program.

In 2012 he was named one of 25 Important Artists of Tomorrow by American Artist Magazine. In 2013 his work was included in the book Painted Landscapes, Contemporary Views by Lauren P. della Monica. His work has also been reproduced in periodicals including, American Artist Magazine, American Arts Quarterly, Art News, American Art Collector, International Artist Magazine and Art and Antiques (Courtesy of PAFA).

Front Room, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 28" x 26"

Cast Hall, Oil On Linen Mounted On Panel, 32" x 36"